Housing Minister Chris Bishop wants cities growing ‘out’ and ‘up’ – but with councils soon able to opt out of the Medium Density Residential Standards (MDRS), Better Things Are Possible author Malcolm McCracken explores how the ‘up’ can be achieved instead

Enabling greater capacity in our plans through intensification is key for unlocking greater housing supply and in turn affordability, as recent studies in Auckland and Lower Hutt have demonstrated. However, the National-ACT Party coalition agreement commits this government to enabling councils to opt out of the Medium Density Residential Standards (MDRS). While there was room for improvement, the MDRS was mostly positive, particularly in enabling housing supply and choice in existing neighbourhoods across our major cities.

I believe that we still need to find a way to make it easier for the market to respond with new supply in areas of high demand in existing urban areas, where the zoning may not be commensurate with the demand. The current plan change process is arduous and time-consuming, in turn being costly and often financially unfeasible for developers to pursue, unless it is a major land holding. While a replacement of the Resource Management Act (RMA) should seek to address this, we need to break down these barriers sooner. So, what could a solution look like, that generally enables councils to opt out in areas, but allows for the market to move more quickly?

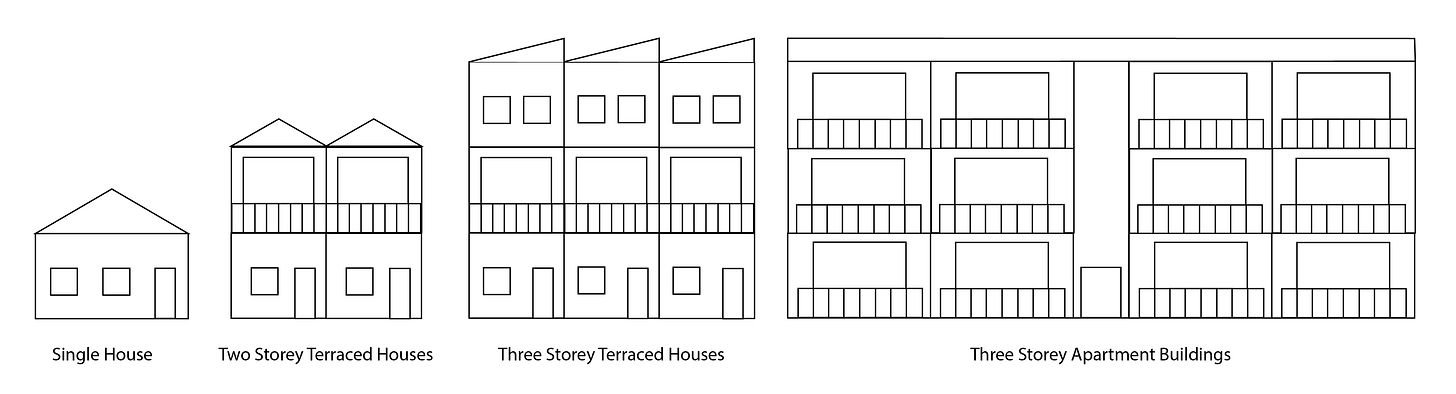

I propose that a condition of a council opting out of the MDRS, in whole or just in certain suburbs, should be the requirement to introduce Graduated Density Zoning (GDZ) to residential land that is zoned below three storeys. GDZ is where, when a developer buys neighbouring sites totaling more than the set threshold, e.g. 1400m2, they can automatically build to a higher density. The details of that can be debated but I believe GDZ should be introduced to enable better housing choice and new supply in every neighbourhood. While resource consent would be required, once the threshold has been met, three-storey apartments and terraced houses would become a permitted activity.

Adopting GDZ could provide several key benefits:

- Larger sites can make it easier to manage the externalities of greater density, which have been some of the driving reasons behind the backlash towards the MDRS. This should see fewer sausage flats7 on single sites, which generally have poor design outcomes and interaction with neighbouring sites. Larger amalgamated sites will enable greater master planning that considers the interaction of outlook spaces with neighbouring properties, limiting driveway crossings and the design of open and communal spaces.

- It enables the market to deliver greater density in areas of high demand and better match this with new supply. While councils can plan through future development strategies for ‘enough’ capacity to meet future demand, this is always based on a range of assumptions, which can never be completely accurate. Amenities and accessibility of an area, along with personal preferences, can change shifting demand greatly. We should design our system to be more responsive and flexible to meet demand. GDZ would be a step towards this.

- Enabling three storeys, as I have discussed many times previously, can enable greater housing choice to be provided. It also enables ageing in place, where you can find housing suited to your needs at different stages of your life within the same neighbourhood.

- It’s worth noting that this can also benefit neighbouring landowners, who could choose to sell together to seek greater profit, which is possible as an amalgamated site is generally a better development opportunity. This has occurred previously, including in Te Atatū Peninsula in 2020 when three neighbours teamed up to sell together to seek a higher price given the greater development potential of an amalgamated site totalling 2427m2. Under a GDZ scheme, this would likely become more common.

How should this be implemented?

GDZ is not new in the New Zealand context. Lower Hutt previously adopted a version of GDZ through Plan Change 43 in 2019. In this plan change, eight locations were chosen for upzoning based on their proximity to shops, schools, public transport and access to parks. These areas were in Stokes Valley, Taita, Naenae, Avalon/Park Ave, Epuni, Waterloo, Waiwhetu/Woburn and Wainuiomata. This occurred through the introduction of two new zones:

- the Suburban Mixed Use Activity Area, which introduced a building height standard of 12 metres (three to four storeys), and

- the Medium Density Residential Activity Area, which introduced a building height standard of 10 metres (plus one metre for the roofline).

Outside of these areas, the General Residential Activity Area zone applied, keeping low density, stand alone houses on sites of at least 400m2 as the primary built form. However, in areas with this zoning, the Plan Change also provided for medium-density housing of up to 8m (two storeys) on sites larger than 1400 square metres through what they termed Comprehensive Residential Development. While I understand the development has largely occurred in the eight primary development areas, many developments have been delivered through the Comprehensive Residential Development, approach, improving housing supply and choice.

The Lower Hutt case study provides inspiration for a more nuanced while flexible approach to enabling medium density in low density areas. I believe, a part of the condition of opting out of the MDRS, GDZ should be a requirement with the standards modelled on the Coalition for More Homes – Alternative MDRS. These standards sought to free up the front of the site for development while introducing greater restrictions to the rear half of the site to minimise impact on neighbouring sites.

GDZ should not apply everywhere. Tier One councils have already undertaken significant work on Qualifying Matters, like floor-prone areas and coastal erosion zones, to exclude these areas from upzoning. These should be exempt from the GDZ, in the same way they were exempt from the MDRS and NPS-UD requirements.

Conclusion

As Donald Shoup notes in his 2008 paper, GDZ “has the potential to ease both the politics of higher density and the economics of land assembly”, the former being the primary challenge that medium density faces in New Zealand. GDZ as proposed in this article, could achieve similar benefits to the MDRS but with greater mitigation of the potential perverse outcomes possible under the MDRS. I believe that GDZ could provide suitable mitigation, in terms of supply and flexibility for the market, to councils opting out of the MDRS. If we are serious about addressing the housing crisis, we need to find pathways to enable density across existing urban areas, GDZ may be that pathway.

Originally posted at Graduated Density Zoning, a condition for opting out of the Medium Density Residential Standards? (substack.com)