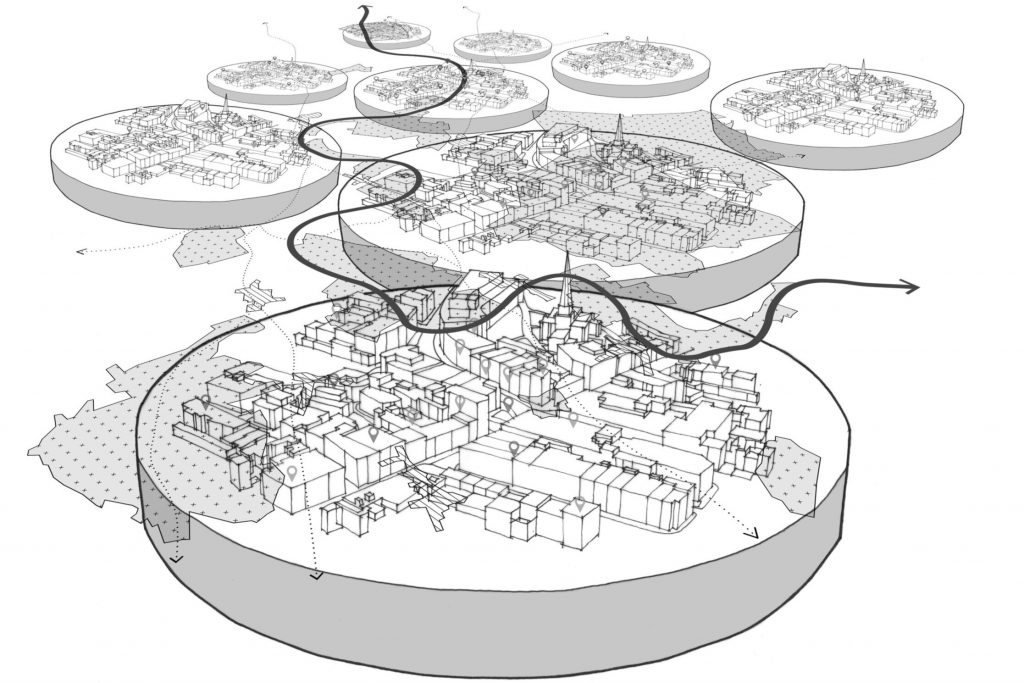

The X-minute city is a global urban planning concept intended to challenge thinking on how we develop, build and manage neighbourhoods, Bayleys says in its latest Total Property publication

Creating urban neighbourhoods where amenities and services are all within easy walking distance of where people live, is bringing value upside.

In its purest and literal form, planners and developers would concentrate on live, work, play models where every touchpoint is within say a 15- to 20-minute walk, bike ride or convenient public transit option of where someone resides.

Diverse and varied business activity, education facilities, healthcare provision, and leisure pursuits would ripple out from residential catchments and any proposed development would be rigorously tested against walkability and connectivity benchmarks.

A University of Canterbury paper The x-Minute City found that 35 percent of Wellington residents live within a 10-minute walk of all amenities, and the average time for any Wellingtonian to walk to all amenities is 14 minutes.

In Auckland, the average time to walk to all amenities is 18 minutes, with 15 percent of residents within a 10-minute walk of all amenities.

Bayleys’ global real estate partner Knight Frank says while walkable cities and neighbourhoods promote healthy sociable lifestyles and communities and assist developers/investors to meet their environmental, social and governance (ESG) targets, the idealistic 15- to 20-minute framework won’t work everywhere as not all cities have the infrastructure to support the narrative.

However, if developers and planners benchmark any proposed development against its fundamental impact on walkability, then efficiencies and benefits will follow.

Knight Frank UK’s Urban Walkability Tool allows different markets or buildings to be evaluated and scored based on their existing access to amenities. It concluded that those markets with a good balance of office, retail and residential space support the notion that successful precincts of the future will be mixed-use, mixed-income, walkable places.

Developers in Vancouver, Canada have focused on creating villages within the city where essential day-to-day requirements can largely be found within a six-block radius, leading to young professionals and others living in these areas to shun car ownership.

Todd Litman from Canada’s Victoria Transport Policy Institute, says the alternative to car dependency is not a total lack of private cars, but a system which makes all transport modes eminently accessible.

A multi-modal model, he says, “allows people to use the best mode for each trip: walking and cycling to local destinations, public transport for travel on major corridors, and automobile when it is truly optimal.”

Meanwhile, the Melbourne Plan is a grand scheme to future-proof that city founded on the 20-minute neighbourhood where walkability allows people to meet most of their everyday needs within walking distance from home. A 20-minute round trip – or around an 800-metre walk each way – was found to be the average distance people are willing to walk to meet daily needs, and inner Melbourne with its high-density living largely reaches this target.

New ways of living

Bayleys national director commercial and industrial, Ryan Johnson says while New Zealand has a long way to go until residents, councils, developers and policymakers ditch car-first thinking, Auckland is showing positive signs of change.

“Walkable catchments and neighbourhoods like Wynyard Quarter, driven by developers Willis Bond, epitomise mixed-use precincts with intensified residential living, office premises, vibrant hospitality and retail options, and effective connectivity to the CBD.

“Further out, Kiwi Property is shaking up Mt Wellington with its mixed-use Sylvia Park precinct where a huge build-to-rent (BTR) scheme will soon deliver long-term rental accommodation next to multi-modal transport options including rail, and high walkability with pedestrian links to its 250-store retail centre.

“It intends replicating the BTR model on a reduced scale at its LynnMall precinct in New Lynn, again to provide choice that optimises liveability and walkability.

“Seeing heavyweight developers, including listed property entities, investing in residential BTR development is a step change away from solely commercial, industrial or retail exposure with mixed-use zoning providing scope for diversification and new property typologies.”

In Takapuna on Auckland’s North Shore, a significant BTR development has been consented with a development agreement between Eke Panuku Development Auckland and the Cedar Pacific and McConnell Property consortium for a 358-apartment development on under-utilised council-owned land. This project has deemed multi-pronged benefits from boosting long-term housing supply to stimulating further investment in this identified growth node.

Eke Panuku has also partnered with Willis Bond on the $400 million, 5,560sqm mixed-use Takapuna Central development, with more than 100 premium apartments to be delivered in the first stage.

“These ambitious developments, coupled with the revitalisation of Takapuna’s town centre and plans for better connectivity across the suburb, give weight to a prime landholding now for sale with Bayleys that has favourable Business – Metropolitan Centre zoning,” says Johnson.

“On offer is 9,482sqm of land held in in eight contiguous titles close to Takapuna Beach with compelling commercial, mixed-use and residential future development options.

“Private developers and other entities will recognise the potential value gains and opportunity to leverage other projects underway in an increasingly self-sufficient suburb which has seen $1.01 billion in commercial investment in the past 10 years.

“Further uplift for retail, hospitality and service providers is expected off the back of an even stronger residential base and the walkability factor which is being enhanced.”

The green commute

Bayleys head of insights, data and consulting, Chris Farhi says more intensive development around key public transport hubs and where existing infrastructure and zoning supports it, is changing the shape and form of our urban environment.

“Auckland Council confirms an uplift in property values since higher density zonings were implemented under the operative Auckland Unitary Plan and there’s been sentiment shifts post-pandemic about how neighbourhoods perform on a liveability scale.

“When people were mandated to work from home, the ability for their essential needs to be met locally was highlighted and some city fringe and suburban locations excelled.

“We saw some suburban locations flourish as town centres effectively took the place of the CBD. Subsequently, with hybrid working models becoming common practice, many are looking to live, work and play in a more contained neighbourhood.”

Referencing a notable demographic attitude shift away from car ownership, Farhi says research shows that younger people are less likely to own a car, or if they do own one, less likely to use it every day.

“A recent study commissioned by rental car firm Avis New Zealand suggests that over half a million Kiwis are ready to step away from car ownership and towards car subscription, which allows access to a car without ownership ties.

“Broadly, Generation Z relies more on public transport, car or rideshares, cycling, e-scooters or walking to get around than those before them.

“The green commute is seen as highly desirable from a health/well-being perspective and for the environment, but naturally has limits for those who may be mobility-challenged and is confronting for those who feel driving is the norm.”

Active commuting supports the reorienting of cities towards a more sustainable model, but requires a fundamental shift in entrenched attitudes says Farhi.

“Twenty years ago when the standalone home was championed, a double garage and additional room to park off-street was standard as multiple-vehicle ownership was commonplace.

“Modern high-density residential models typically have less space for cars so over time this is reinforcing the wider consumer trend towards less dependency on owned vehicles.”

Both up and out

Auckland Council chief economist Gary Blick says the Auckland Unitary Plan (AUP) was a bold change in 2016 to boost housing capacity by rezoning much of the city’s residential land to allow for higher-density housing.

This “upzoning” added housing capacity in existing urban locations, some of which have proximity to public transport and are within reasonable walking distance of services and amenities such as town centres and green spaces.

“Recent research from the University of Auckland points to the AUP as being significantly responsible for a surge in new homes,” Blick says.

“Around 22,000 new homes consented from 2016-2021 were a direct result of the AUP and would not have occurred in its absence – that’s around one-third of the 67,000 new dwellings consented in residential zones over that period.

“This has been driven by new multi-unit dwellings, in particular townhouses, as people choose to live in locations upzoned for higher density living, to get closer to employment, transport options, and amenities.”

Introduced under Labour, the National Policy Statement for Urban Development (NPS-UD) 2020 is a government directive to allow residential intensification in main cities. The focus on “quality compact growth” would see more townhouses and apartments developed along rapid transport corridors and where existing infrastructure supports growth.

Blick says the NPS-UD builds on the AUP by allowing for an even wider variety of homes in some places.

“Auckland Council’s response, known as Plan Change 78, is before an Independent Hearings Panel, and we’re yet to see the outcome of that.

“It proposes allowing up to six storeys of residential development, such as apartment-style living, in the walkable catchments around many of our town centres and rapid transit network stations, to allow more people to access jobs, transport, and amenities like shopping, parks, or schools.”

Housing affordability and generational choice are also of note here, says Blick.

“When there are more of these development opportunities, we get competition among landowners and more choice for current and future households. Over time, this can support improved housing affordability.

“It also provides people with more choice across life stages, from young professionals who want to get on the property ladder, to families and older people who may be downsizing.

“In turn, more people having the choice to live closer to jobs, transport and services is positive for our overall productivity and our wellbeing as a society.”

Productivity and well-being are noted here as contributing value to the community and society, beyond the economic value uplift created by intensification.

“The evidence is quite clear, locations that are closer to the things people value – such as employment, transport options, and amenities – tend to have higher land values per square metre,” says Blick.

“If we allow that land to be used more intensively, then the potential productivity or yield has been increased, and the land value rises to reflect that opportunity.”

Public sentiment

Wellington’s central core is only around two kilometres in diameter yet much of the inner city and immediate fringe areas are still underutilised – note car yards that stretch along Kent and Cambridge Terraces, for example.

Discouraging car dependency was behind the now-axed Let’s Get Wellington Moving campaign, but there is still lingering support for initiatives that move people – not vehicles – more efficiently around the city, and for policies that support upzoning in the capital.

Wellington’s District Plan is currently under review with decisions around density zoning, walkable catchments, character precincts, and development overlays including height limits pending.

Central government wants council to plan for more homes within “walkable catchments” of the CBD and to further move the dial on density, following Auckland’s lead. Advocacy groups like City for People are calling for more housing in areas where people can walk, bike or bus to work, and public marches are planned by those adamant that upzoning would contribute to lower emissions, lower infrastructure costs, reduced costs of living, and ultimately lead to a more vibrant Wellington.